Guest Post: David Alexander Robertson's Graphic Novels on the Life and Death of Helen Betty Osborne

Still Sharing Helen Betty’s Story: David Alexander Robertson’s Graphic Novels on the Life and Death of Helen Betty Osborne

Jessica Fontaine, Research Fellow

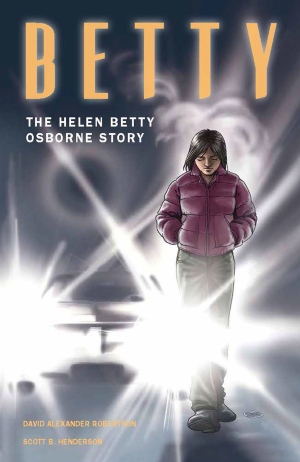

In an interview on CBC’s Unreserved with Rosanna Deerchild, David Alexander Robertson, author of two young adult graphic novels about the life and death of Helen Betty Osborne, urged listeners to both read and share the knowledge contained within Osborne’s life’s story. More than the basic facts or narrative of Osborne’s murder in 1971, both of Robertson’s comics seek to inform readers of the roles that racism and indifference play in violence against Indigenous girls and women. Comparing the shifts in narratives and contextual frameworks that Robertson employs in 2008’s The Life of Helen Betty Osborne: A Graphic Novel and 2015’s Betty: The Helen Betty Osborne Story illustrates how much work still needs to be done to secure the rights and safety of Indigenous women in Canada.

Education is central as a theme and purpose in both depictions of Osborne, but it is particularly prominent in Robertson’s first telling. Robertson stresses Obsorne’s desire to become a teacher in order to provide education in her community in Norway House, Manitoba. It is because of this drive and the lack of educational infrastructure in Norway House that Osborne leaves home to attend school, first at Guy Hill Residential School and then in public high school in The Pas.

Robertson sets The Life of Helen Betty Osborne within a school context. The story shows a light-haired student struggling to learn about residential schools, institutionalized racism, and social discrimination in The Pas through the life and death of Osborne. The student’s gender is ambiguous, suggesting that the story of Helen Betty Osborne is one with which every student should connect. Red, blue, and green speech balloons and text boxes, accompanying almost all of Madison Blackstone’s illustrations, emphasize what can be learned from her murder. The green text in particular shows the thoughts and emotions of the student as they try to comprehend and give sense and meaning to Osborne’s death. The text focuses heavily on the positive legacy of Osborne, particularly extolling how an inquiry into the subsequent investigation of her death concluded that racism, sexism, and indifference contributed to mishandling her case. As such, the text’s educational tone almost suggests that so much has changed as a result of Osborne’s death that discrimination and violence against Indigenous women is no longer an issue.

However, Robertson’s return to Osborne’s story in Betty, seven years after the first graphic biography was published, makes it clear that this is not the case nor his belief. Upon witnessing thousands march in Winnipeg to honour Tina Fontaine, a 15-year-old Indigenous girl whose body was pulled from the Red River in August 2014, Robertson felt the need to “re-contextualize [Osborne’s story] again against today’s epidemic.” He opens Betty with representations of the march and of a boy reading a Facebook page. This introduction reveals not only the social media discussions of distress surrounding the numerous disappearances and murders of Indigenous women, but also the destructive and racist comments that accompany these conversations.

The need for empathy and action are central motifs in the recent graphic biography, as Betty loses Robertson’s previous work’s instructive feel. Robertson does away with the colourful, didactic text and instead focuses on the images to tell a two-fold story of hope and hate. In Betty, Robertson sets a quiet narrative of Osborne’s last night against the raucous partying and violence of the four men who killed her. She spends time visiting with friends, dreaming of the future, and walking down the street, leaving her soft footsteps behind her. Conversely, and because of the sparse dialogue throughout the comic, the men’s drunken discussions about “cruising for some squaw” to have sex feel both potent and ominous.

Scott B. Henderson’s black and white, action-centered illustrations send the two narratives on a collision course, fuelled by the men’s racism and misogyny. Henderson depicts their car’s headlights as blinding and predatory, particularly in the final sequences in which the men kidnap and then beat and murder Betty. Although the majority of the violence takes place outside of the comic’s panels, the comic retains a sense of brutality because of the aggressive build up to the murder and the use of onomatopoeia in the final scenes. Multiple renderings of the word “Thump”, written in a horror-style font, fill an image on the rear window of the car and connote the intentional, repeated assault Betty endured.

Although Helen Betty Osborne is not included in the 1200 cases of missing and murdered Indigenous women and girls compiled by police over the last thirty years, Betty joins the calls action to end the violence. Concluding with an image of the vigil for Tina Fontaine in front of a Winnipeg memorial for the missing and murdered Indigenous women, Robertson asks, “But what can we do?” By asking this question, Robertson implicates the reader and challenges their passivity. For Robertson, both the education provided in The Life of Helen Betty Osborne and the empathy incited by Betty require a response from each individual in order to create and sustain social change.

Other projects calling attention to the issue of Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women, Girls, Trans and Two Spirit People in Canada (MMIWGT2S):